2018 Update: Botham Shem Jean is shot in his home by an officer who “mistakenly” thought his apartment was hers. Instead of releasing information about the shooter-officer, they attempt to smear the victim. Around the nation, police officers are pictured throwing up the “white power” sign. In my article on white supremacists in law enforcement and the military, NPR noted that in “the 2006 bulletin, the FBI detailed the threat of white nationalists and skinheads infiltrating police. The bulletin was released during a period of scandal for many law enforcement agencies throughout the country, including a neo-Nazi gang formed by members of the Los Angeles County Sheriff’s Department who harassed black and Latino communities. Similar investigations revealed officers and entire agencies with hate group ties in Illinois, Ohio and Texas. Problems with white supremacists in law enforcement have surfaced since that report. In 2014, two Florida officers — including a deputy police chief — were fired after an FBI informant outed them as members of the Ku Klux Klan. It marked the second time within five years that the agency uncovered an officer’s membership in the KKK.” In June 2015, two Alabama police officers left the department over ties to white nationalists. Last month, Alabama police officers were suspended for making a white power gesture in a photo. Also last month, a Washington County Sheriff deputy was fired after wearing clothing associated with a white pride group. A police union president called Black Lives Matter protesters a “pack of rabid animals”. A Kentucky police officer called a black teen a “wild animal that needs to be put down.” His Facebook page demonstrated “deep-seated bias against minority communities.” So much for Officer Friendly.

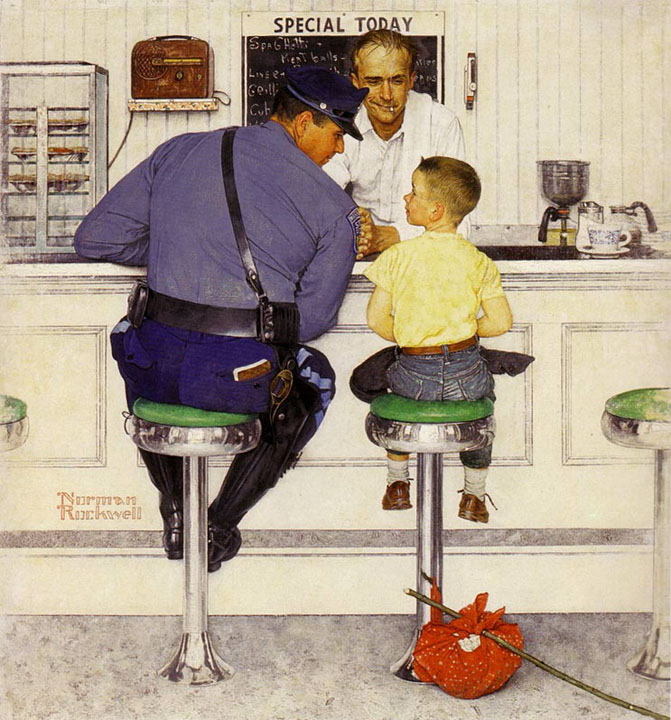

I recall visits from Officer Friendly in grammar school. Unfortunately, for many people of color, especially African-Americans, to serve and protect is the last thing associated with our police force.

I approach this topic as a woman of color. I grew up in racially segregated Chicago. Although it was not the South, there were still neighborhoods where blacks were not welcomed. My first encounter with racism was as an 8-year-old on a family vacation to visit relatives in the South. It soured me on returning, and whenever I hear a certain drawl, it instantly revives memories of our almost-encounter with the KKK. When I was a preteen shopping for an eighth-grade graduation dress in the Chicago suburbs, a white sales associate refused to serve me and my mom. She told us, “We don’t have anything for boys.” My mom responded, “She is not a boy.” The saleswoman replied, “We don’t have anything for you here.”

Growing up on the far South Side, I recall hearing my dad and other male relatives warn about the danger of being pulled over by police from a certain precinct. It was notorious for police torture under Police Commander Jon Burge. Many black men were tortured into confessing to crimes they never committed. They served time for crimes all under the guise of a traffic-violation pullover.

During my senior year in high school, my family bought a home in a working-class and lower-middle-class neighborhood near Marquette Park. (Marquette Park was infamous for its treatment of Dr. Martin Luther King on his visit to the city.) It was 1988, and we were the first African-American family on the block. It might as well had been the 1960s, because it felt reminiscent of Lorraine Hansberry’s A Raisin in the Sun. Our family’s car frequently had slashed tires courtesy of an Archie Bunker-type neighbor. Shortly after moving on the block, while coming home from Sunday evening’s church service, we were pulled over a block from the house. My dad was driving, with Mom in passenger seat and me and my sisters in the back. Dad instructed us to keep quiet and make no sudden movements. The cop approached my dad’s window and asked, “What are you doing in this neighborhood?” My dad explained that we were heading home and lived around the corner. The cop reviewed my dad’s license. He then claimed that he’d pulled my dad over for driving erratically and alleged that my father was drunk. My father had stopped drinking after joining church years earlier. I was 16 and yelled from the back seat, “You’re lying. My dad does not drink or smoke.” My parents shot me a look as if I had just endangered the family. Fortunately my outburst worked. The cop did not give my dad a ticket. He said, “Well, be careful driving.”

When my sister had her boys, I worried for them. Being a black male in the city meant that targeting or profiling by police would be a reality regardless of what you wore or how articulately you spoke. One nephew was tall for his age. By the time he was 11, he was already 6 feet tall. I knew the police would not see an 11-year-old boy but a 6-foot-tall black thug. I began putting my attorney business cards in my nephew’s jackets, backpacks, and jeans. I told him, “If the cops stop you, tell them your name and your address and that your aunt is a lawyer and that you want to speak to your lawyer now. You keep repeating that like you are Rain Man wanting to see Judge Wapner at 3 p.m.”

Shortly after passing the bar exam, I came home from work and changed out of my suit into casual attire. I was living with my parents while apartment hunting. A few minutes after I undressed, there was a knock at the door. Our neighbor, a single mother and practicing nurse, was upset. The cops had shown up and taken her 13-year-old son to the police station and would not let her see him. By this time, the neighborhood was more diverse. The kids on the block were a motley crew of blacks, Hispanics, and whites who played on the sidewalk. They’d been playing football in the street when the cops had arrived, broken up the game, and taken our neighbor’s son to the precinct. I grabbed my attorney credentials and went to the station with the neighbor. Even though I followed protocol, showing my attorney credentials, the cops were rude and belligerent and refused to grant me access to the boy. At that point I told the cop that I wanted his badge number and that of his supervisor to report them. I also let it drop that I worked with Johnnie Cochran. After a few moments the supervising youth officer came and apologized. Why did I have to go through that?!

My personal encounters with the police have not been pleasant, especially when “driving while black.” It usually takes me using the “attorney card” before I am free to go. I recall visits in grammar school from “Officer Friendly.” He would give us tips on how to be safe when walking to and from school. Officer Friendly told us that in an emergency, we should seek out a police officer, because their job was to serve and protect. What ever happened to Officer Friendly?

In Chicago, I lived in the South Loop, a few blocks from former Mayor Daley’s residence. One evening I walked into my apartment as it was being robbed. I encountered the robber head-on, and instead of running, I interrogated him. Do not ever do this! Fortunately, I was not injured, but he walked away with my valuables (jewelry given as gifts for graduation and passing the bar). However, the response by police left me speechless. First the cops said that since I was not injured, there was no need for them to come. I could just file a report over the phone. After I insisted, two cops showed up. My white neighbor witnessed part of the robbery and was there when the cops arrived. The cops asked for a description of the robber. As soon as I said, “African-American male about 5-foot-3,” the cops interrupted me. One cop asked, “Are you sure your boyfriend did not do it?” At that point I was ready to turn into an angry black woman. My neighbor pulled the cops aside and said, “Do you see that degree on the wall? She’s a lawyer. See that picture? That’s her and Johnnie Cochran. I suggest you change your line of questioning.”

Emmett Till, Sean Bell, Trayvon Martin, Oscar Grant, Michael Brown, Ezell Ford…. When will it stop?! As a black woman I am fearful of giving birth to a son. If my son became a victim of police brutality, it would take all of heaven to stop me from going to the dark side. As an attorney, I know that justice is not blind; it is biased. For the same crime, a black person is 30-percent more likely to end up in prison than a white person. Even when it comes to discipline in schools, black students are given harsher punishment than white students. It does not matter if people of color are well-dressed or wearing hoodies. There is a societal acceptance of the belief that underneath the suit or hoodie, we are prone to bad behavior.

Black teens are shot dead for walking in the street. White teens are caught breaking into an upstate New York mansion and having a party with drugs and alcohol, vandalizing the home, but not one of those teens was arrested. Instead, some of the parents threatened and harassed the homeowner for, in the homeowner’s words, “[ruining] their kids’ college plans.” Really?! Yet Michael Brown and Trayvon Martin are a threat to society. Officer Friendly decided not to ruin college for privileged drinking and drugging teens, but ruining the college plans of Michael Brown is OK?

Ferguson police released a video allegedly showing Michael Brown engaged in an aggressive robbery. Even assuming that the person in the video is Michael Brown, that does not negate the wrong done by police. Ferguson police, against DOJ advice, released the video because the press wanted it. Yet when the press wanted the name of the officer who shot Michael Brown six times for walking in the street, they refused to release that information. Let us not forget that a kid is dead for walking in the street!

W.E.B. Du Bois wrote:

The history of the American Negro is the history of this strife, — this longing to attain self-conscious manhood, to merge his double self into a better and truer self. In this merging he wishes neither of the older selves to be lost. He would not Africanize America, for America has too much to teach the world and Africa. He would not bleach his Negro soul in a flood of white Americanism, for he knows that Negro blood has a message for the world. He simply wishes to make it possible for a man to be both a Negro and an American, without being cursed and spit upon by his fellows, without having the doors of Opportunity closed roughly in his face.