There are many negative media images about black boys and men. However, I know black men who are being the village to our youth. I grew up watching the men in my neighborhood reach out to young kids in the community. If they were hanging out, the older men would say, “Young blood, what you doing? Come here let me show you how to fix cars.” My father was a carpenter, so he would offer to train them in carpentry and bring them on the site to get jobs as construction workers. Other men in the community would do the same. The media inundates us with “black on black crime,” but never tells talks about white on white crime. Law professor, attorney, and civil rights activist Nekima Levy Pounds noted, “Eighty percent of white people killed are by other white people, but it’s never brought up or made like there is a special “pathology” within the white community like they do for black people. Whites killing whites is an indictment against the individual not the community at large. That is not true for blacks. If a black person commits a crime, then there must be a certain pathology within the black community.” We need to change the narrative and make sure that our young boys and men are exposed to positive images of black brotherhood.

The death of my eldest nephew last summer devastated me. All of my volunteer, youth mentoring, and coaching was because of him. This nephew was my first baby, my most spoiled. He always brought other kids around. I would tell him that auntie time is just for you guys. He would say, “But they don’t have anybody.” As I helped my sister and her husband with funeral arrangements, she said she did not want any remarks. Through a miscommunication remarks were allowed. It was then that I saw how my nephew continued my father’s legacy of being his “brother’s keeper.” At his funeral and the Navy Memorial, over and again young people and his commanding officers repeated how he was a leader and brother to all. Several friends commented that when things were bad in their life, my nephew would say, “If you don’t have family now you do, I’m your brother.”

I was surprised at the young men, military and motorcycle buddies of my nephew. One in particular was dubbed “daddy daycare” for looking out for my great nieces. A few months after my nephew’s death, his daughter turned one. She had two parties. One with us and then flew back to his base city because her godfather and godmother (both Navy) threw her another one. My nephew’s military and biker brothers showered her with gifts. This is what I know of black brotherhood. In speaking about my nephew, his friends and commanding officers said that my nephew could get on their nerves, but he was valued and a leader. Isn’t that what brotherhood is all about? Getting on your brother’s nerves, but holding them down when life is hard.

My nephew and his friends are not an anomaly of black brotherhood. They are what made black excellence in science, arts, medicine, politics, music, and innovation. Black Wall Street existed because slavery and Jim Crow taught us that we are all we have. The Black Panthers origin was rooted in the fact that blacks were not entitled to the same social service benefits as whites. Therefore, the Black Panthers took on the role of social service and after school program providers. The Black Panthers, Martin Luther King Jr., and Malcolm X’s emphasis on brotherhood and unity within black neighborhoods was so strong that J. Edgar Hoover used the FBI “to prevent the rise of a ‘Black Messiah’ who could ‘unify and electrify’ the black community.” Each one, teach one is the village mentality that sustained our survival in an America that still hinders our full enjoyment of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. Yet, with every obstacle to prevent our progress and divide us, still we rise!

Black men continue to invest in the black community. Colin Kaepernick lost his job in the NFL for taking a knee to highlight police brutality similar to the sacrifice of Tommie Smith and John Carlos before him. Musical legend Prince was instrumental in bringing coding programs to the inner city via #YesWeCode and supporting black nonprofits and communities including Black Lives Matter through his charitable work. Prince was an advocate of black ownership choosing to bring his musical catalog to Jay-Z’s Tidal noting, “Once we have our own resources, we can provide what we need for ourselves. Jay Z spent $100 million of his own money to build his own service. We have to show support for artists who are trying to own things for themselves.” Chance the Rapper and Colin Kaepernick’s celebrity status help bring the conversation to a larger audience. However, every day black men are leading the charge, changing the narrative, investing in the community.

BLACK MEN AS FATHERS AND FAMILY MEN

My previous article was on reclaiming the black family. Last week, a white collegiate tennis player responded to his opponent, a black player from a historically black college (HBCU) by saying, “At least I know my dad.” There is a stereotype that black children are fatherless or on welfare, when the largest group of welfare recipients are white. Being raised in a single parent home does not mean the absence of a father or father figure. The black community has always believed that it takes a village to raise a child. Uncles and grandfathers fill the void. A benefit of social media is the ability to promote positive black narratives. Check out The Black Man Can social media page which is filled with black men loving their wives, fathering their children, and supporting their brothers.

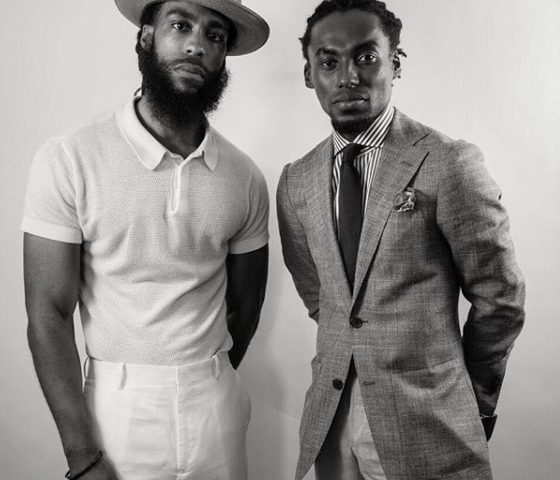

Kells Barnett, founder of #TakeCareofHarlem

BLACK MEN TAKING CARE OF THE COMMUNITY

Most heroes are everyday people who do not wear a cape. One such individual is Kells Barnett, a Harlem native whose commitment to Harlem started a movement, #TakeCareofHarlem. From toy drives, backpacks and school supplies, dresses and suits for prom, cleaning Lenox Ave, to brown bag lunches, #TakeCareofHarlem is about “dope stuff Harlemnites are doing for the community.” Kells said that he and friends that grew up in Harlem “wanted the community to flourish and not have outsiders dictate what the community needed. Those voices needed to be from the within the community as gatekeepers.” Kells is also a designer for 5001 FLAVORS and co-owner of Harlem Haberdashery. Kells and the Harlem Haberdashery family have a commitment to Harlem that is determined. He is in the community, walking the same streets he grew up on, accessible to the community. Kells love for Harlem and making sure that Harlem thrives is part of his DNA and Harlem Haberdashery. Their annual Masquerade Ball benefits Harlem Hospital.

Devale Ellis and his brother, Brian Ellis, used their college football and NFL experience to start Prototype Mentorship, a sports program to get young black kids into college. Devale played basketball in high school, but was not six feet tall. He said, “I realized that you did not have to be LeBron James to get your college education paid. I switched to football and ended up playing football at Hofstra. I was in the NFL for four years. My goal was to make the money and set myself up so that I could have the financial means to be independent once I left the league. When I went to the NFL, I was not trying to be Hall of Fame. I wanted access to the 1% to find out how they built their wealth as a lawyer and executive without being an athlete. I noticed the executives keep wealth in the family. I sat back and was very quiet, then I asked questions about how did you start your company? Building a business is hard work. You may not reap the benefits, but your kids will. You build the business for the kids to take over. Use the building time to teach your children. Instead of drinking the Kool-aid about going into debt to go to college, teach them to be entrepreneurs. I wanted to be a “nation builder” and pay it forward within our community as well.” Prototype Mentorship uses a sports regimen to instill academic discipline and excellence. Kids in their program go on to college and many enter the field of education.

Black Man Can, Take Care of Harlem and Prototype Mentorship are but a small representation of many other black men dedicated to family and community. As Angie Stone sang in Brotha, “Black brotha, I love ya. I’m so proud of you. I love you for staying strong, you got it goin’ on.” #BlackMenSmiling giving a sista’ chills.

Below images from photographer Kay Hickman illustrates everyday brotherhood.