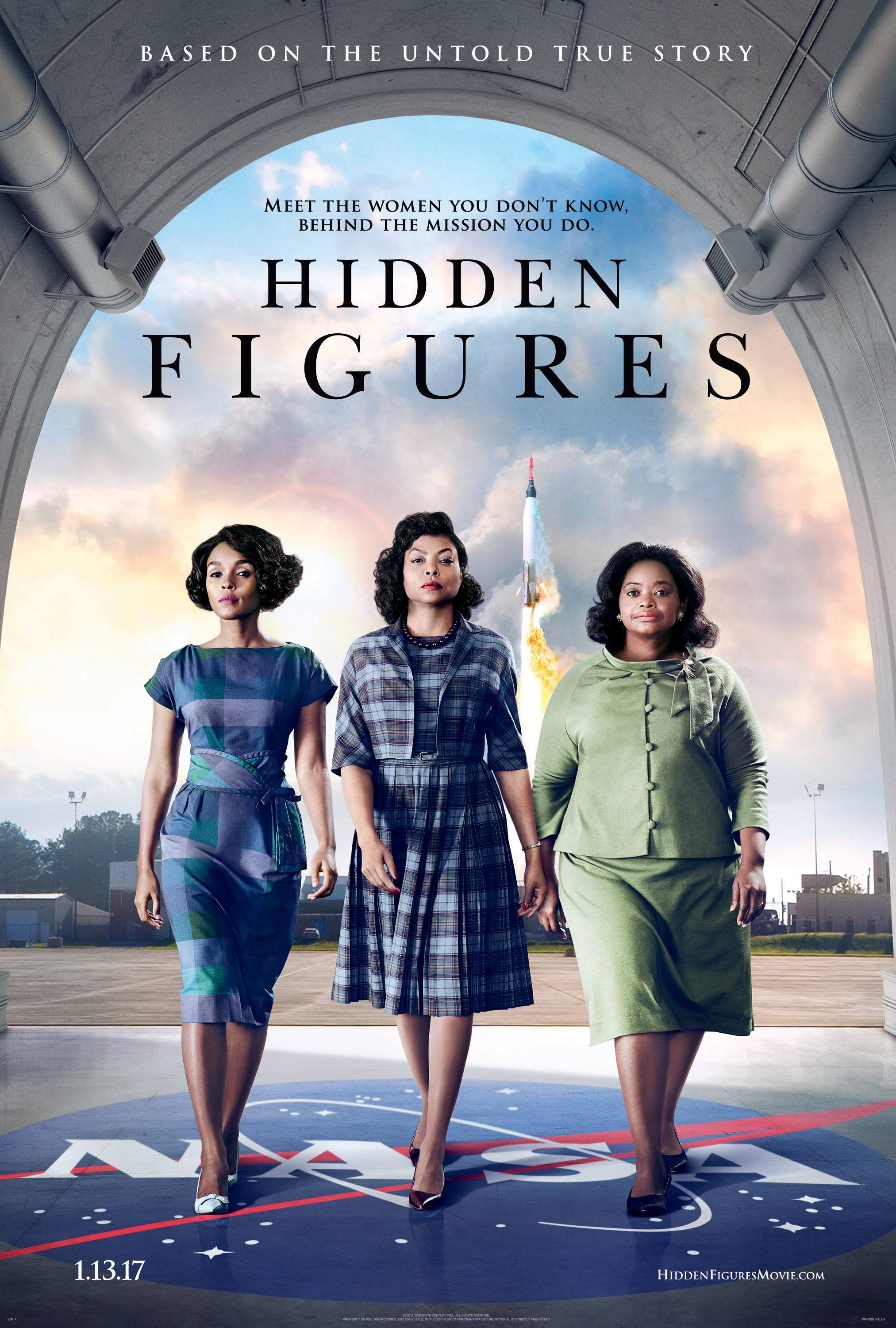

Hidden Figures is a book by Margot Lee Shetterly turned into a movie based on the story of black women working at NASA in the 1950s space race between the US and the former Soviet Union (USSR). Representation matters! As a young girl, I remember that my pediatrician, a West Indian woman, encouraged my mom to put us in science programs. She was the only woman doctor I had met until I became an adult. I saw plenty of women nurses, but not women doctors. I would have greatly benefited from knowing the stories of Kathleen Johnson, Dorothy Vaughan, Christine Darden, and Mary Jackson. If their stories were published years ago, I dare say Mae Jemison would not be a rarity.

Two of my nieces are math and science fans. I wanted to write an article to inspire them to pick up where Mrs. Johnson, Vaughan, Darden, and Jackson left off. I want to encourage more young girls to soar into space, code, and build mind boggling feats of engineering in STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering, Math) professions. I also want girls to be comfortable in their skin in a typically male dominated profession that tends to denigrate women. We have seen sexism rear its ugly head in STEM when Adria Richards complained at a tech conference igniting Donglegate and when Isis Wegner was featured on her company’s website. Even SXSW canceled panels on sexual harassment in tech’s gaming sector.

We must do better to empower our girls and women. As I once told a group of networking women, “If we don’t see the value of investing in ourselves, then no one will.” To that end, I spoke with Ellane J. Park, Ph.D, a professor of Chemistry at Rollins College, Dawne Collier-Dupart, MD, an OB-GYN, and Cinthana Kandasamy, a current medical student about tips to encourage young girls, particularly girls of color, to thrive in STEM.

Who runs the world? Girls! Okay ladies let’s get in formation, lean-in, and mentor young girls dreaming E=mc2.

What made you want to pursue an education in STEM?

Ellane Park (EP): At the age of 5, my mom said I declared that I wanted to be a doctor. I was intrigued by medicine. I loved all my science classes in high school. In college, intending to become a doctor, I took organic chemistry and enjoyed the thrill of solving problems. I loved the way organic chemistry was like putting together pieces of a puzzle in a creative way.

Dawne Dupart (DD): My family members were educators and teachers. I always liked math and science not knowing what I wanted to do, I kind of fell into medicine.

Cinthana Kandasamy (CK): Math and science were my favorite subjects in school. I participated in science fairs and math competitions all throughout elementary, middle, and high school.

Who was your mentor?

EP: My dad has a master’s in biomedical engineering. That helped, knowing someone in my family with a STEM background. At Wellesley College, my chemistry professor became my research advisor and encouraged me to pursue a Ph.D. after spending more than year doing research in his lab.

DD: In college, all of the math and science majors I knew either chose engineering or pre-med. I knew I didn’t want to be an engineer, so I chose pre-med not thinking about being a doctor just not engineering. A friend who was a year ahead and an engineering major told me if I was considering pre-med that I needed to attend this summer immersion program for math and science students of color. You spent the summer at Case Western University shadowing medical students and doctors and preparing for the MCAT. Once I participated in the program, I was hooked! It was empowering to see medical students and doctors that looked like me and were succeeding.

CK: My dad is a research scientist in plant genetics. I would go with him to his research lab on weekends and learn about his research. He was always encouraging once I knew I wanted to pursue medicine.

What obstacles did you overcome?

EP: I went to an all-women’s college, Wellesley. Being in an environment of all female peers built confidence. The obstacles were more internal. I believe women can struggle with the “imposter syndrome” of whether we are good enough to succeed. Talking with my mentors and friends helped. STEM requires a lot of hard work. You have to not give up and keep at it.

DD: Although I attended a great college prep parochial school, Northwestern is a hard school, especially if you are in the math and science program. It wasn’t called STEM when I attended college. Although you’re smart, you have to kick it up a level, settle down and focus on studying. My first quarter I partied a bit much and neglected my studies. My first quarter grades were not good. I went and spoke with the Dean without telling my parents. He was not encouraging at all. He basically told me that I should consider an alternative major and put off med school. What I didn’t know was that a few days later, my parents went to the Dean. They said that I was a good student and that we needed to develop a plan to get me back on track. My parents noted the Dean was not helpful, so my parents along with a biology professor worked with me to get me back on track. Had I listened to that Dean, I would not be a doctor. I had to show him that I was going to do it.

CK: I was a Biology major and declared pre-med. I was fortunate that in undergrad, my classes were a nice mix of men and women. However, that may be because I graduated recently and there are more women in STEM.

Was sexism a problem?

EP: For undergrad, that was not an issue attending an all-women’s college. Post college, I did not encounter blatant cases of sexism, but some subtle bias. So it was important that I made a strong case for whatever point I needed to make (i.e., present facts, evidence to back up statements) in navigating a male dominated industry.

DD: In high school, one of the Jesuit teachers said that my eyes were so loving that I would make a good nurse. I replied that I intended to be a good doctor. He would have never told one of the guys in math/science they would make a good nurse. In med school, it was never specific to me, just more of intimidation. We practiced on cadavers. My partner and I went in on the weekend to practice. Although there were other cadavers, a group of four guys would bogart the cadavers and take over even if you were working. When they entered the lab, my partner and I continued working on our cadavers. Eventually, the guys came over as if they wanted the cadaver asking if we were using it. We said yes, stood our ground, and they moved on to another cadaver. Another incident was when the professor asked a question in class that initially no one else knew and I answered. A male colleague approached me afterwards incredulous like “How did you know the answer?” I refused to explain my intelligence. Like everyone else, I studied the material and read it.

CK: Now that I am in the medical field, people often assume that I am studying to be a nurse and not a doctor. People also ask me how I am going to balance being a doctor and future wife/mother. Male med students aren’t asked that. I am finding it to be a consideration in some male dominated professions like anesthesiology, neurosurgery, and orthopedics. Ortho and neuro have longer residencies and typically mean unpredictable hours. I have spoken with women in those professions and they have said that it was difficult during their training being in the minority. Is that an environment that I will be able to thrive in? It is definitely a consideration when trying to narrow down my field of specialty.

What advice would you give high school girls interested in STEM?

EP: I would seriously advise attending an all-women’s college like Wellesley, Smith, Barnard or Mt. Holyoke. Not only did I attend one, but I also taught at one. The advantage is that gender is not part of the equation in determining whether you are capable in STEM. The real question becomes: “Do you have the (nerdy) passion, hard work, and some level of talent to be successful in STEM?”

DD: Take as many math and science classes and participate in as many STEM prep programs as you can. Join mentor programs for girls to be immersed. Learn how you can apply your skills to a profession.

CK: Explore all the possibilities because there are subspecialties within fields that you might not have considered. Volunteer at hospitals. Try to get summer internships for STEM programs.

What tips for you offer college women in STEM?

EP: First, you must have the character and temperament. By that I mean that you are bound to struggle with failed experiments in science so you need patience and endurance. You want to press on and learn from trial and error. Second, talent and ability alone without hard work will not equal success. I believe skill balanced with hard work leads to success. Loving the field helps. Lastly, mentors are important. As a professor, I am constantly telling students to come see me during office hours. At a small liberal arts colleges, like Rollins (where I teach), professors are there to guide you through the challenging content covered in class but also to help you navigate your life’s career plan. I often walk students through the process of applying for research opportunities and internships in preparation for post-college life.

DD: First, join organizations that align with your interests and career goals. They give helpful tips of the trade and provide more information about your field of interest. Second, develop good study habits and learn how you need to study. Join a study group to maximize resources. Lastly, consider taking a year off between college and med school. I aced the MCAT, but I was so tired from college, studying, and MCAT prep. I needed time to relax and get mentally ready to start med school. I liked studying and was eager to return after my year off. To stay close to the medical profession, I worked as a secretary in a hospital.

CK: Be involved and engaged in research, projects teams, and other STEM organizations. Be proactive and seek out different professionals in other fields to ask for advice. Start building your network community. STEM is very challenging and can be daunting. Don’t be afraid to ask for help and utilize resources available. Develop good study habits and learn to manage your time and schedule. This will help you succeed in med school.

Post-graduation, what is necessary for professional development?

EP: Constantly seek out mentors that speak truth in you and organizations that network and give back to younger girls. In graduate school, I co-chaired the Women in Science student organization. We coordinated programs for underserved middle school girls in New York City to introduce them to the world of STEM and connect them with female graduate students and faculty.

DD: Mentorship is key. Join professional women organizations in your field. Try to find someone in your profession that will take you under their wings and mentor you.

To summarize: Network! Every August, I send Advice for College Freshmen to students I have mentored. You should not be a stranger to your professors. They likely are aware of internships, jobs, and will be a reference for you. Get to know your instructors and your peers. Someone in your study group may be the person that assists you with a summer job or scholarship lead. As I told the women networking group, “Invest in yourself, invest in those that have invested in you, and spread the word.”

To assist girls and parents in their journey to STEM greatness, below are a few resources. Girls, go run the world!

Black Girls Code – nationwide program to increase the number of women of color in the digital space by empowering girls of color ages 7 to 17 to become innovators in STEM fields.

Coastal Studies for Girls – a semester long science and leadership program for tenth grade girls.

CodeNow – nationwide program that partners with tech companies across the US to deliver fundamental programming skills to underrepresented youth.

CoderDojo – nationwide programming clubs for young people 7-17 to learn how to code, build a website, create an app or a game, and explore technology in an informal, creative, and social environment.

DYN Digital Divas – Chicago program that engages middle school girls in STEM programming through a series of design projects.

Digital Undivided – providing high potential Black and Latina women entrepreneurs with the network, coaching, and funding to build and scale their technology companies.

Disrupt Harlem – a program to teach Harlem youth how to code.

YesWeCode – nationwide program inspired by late musician Prince to help young women and men from underrepresented backgrounds find success in the tech sector.

Youth Led Tech – Chicago technology mentoring program for youth ages 13-18.